We’re having a glorious spring up here in North Yorkshire. Back-to-back sunshine has meant I’ve spent many hours gardening - which is partly why I’ve taken a week off from writing and Substack. I’ve been digging out couch grass rhizomes from a border (a hellish, interminable activity), and painting a 25m fence, and, while doing so, I’ve also been thinking about relationships between women and gardening through history - and how men have muscled in, disrupted, exploited and hindered that relationship, and how they still do. So this week’s ‘No Women Allowed’ post - which is part of my series for paid subscribers about the bans that men have imposed on women’s presence in certain activities or places, and how women have resisted - is about men’s attempts to appropriate gardening, botany and horticulture for their own sex, alone.

Today, the idea of domestic gardening tends to conjure up images of retired women in their back yards; whereas the upper and professional echelons of gardening are associated with men, such as presenters Monty Don and Alan Titchmarsh, designer Piet Oudolf, or rose-breeder David Austin. As this suggests, gardening does not just mean one thing. It is a vast term that comprises myriad sub-categories and related activities, such as botany, ornamental gardening, kitchen gardening, agriculture and agronomy, garden design, landscaping, forestry and so on. Similarly, the connotations of the word gardening have changed over the centuries so that, in some periods, gardening has been associated more with domesticity; in others, with scientific research; or with the agricultural production of food; with the design of large landed estates; with the imposition of order onto wildness; or with the accommodation of nature and the needs of the ecosystem. All these guises and meanings of gardening are profoundly riven along lines of gender, class, (dis)ability and race. Certain activities have been considered suitable for working-class women, but not their upper-class counterparts; or for white women, but not Black women, or vice versa. And there are certain forms of gardening that men have tried to appropriate for themselves with particular vigour.

How Men ‘Redeemed’ Flowers from their Girly Associations

Here’s a prime example: for much of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, botany was widely considered to be a suitable pursuit for middle- and upper-class women. Illustrating flowers was thought to be refined, delicate and detailed, well-suited to women’s apparently superior fine motor skills, and it utilised upper-class women’s education in painting, as well as keeping them close to home. Jane Colden (1724-1760), for example, lived with her family on a 3000-acre farm on the Hudson, and in 1753 was systematically describing around 140 wild plants per year, with the approval of her father, who considered that ‘Ladies are at least as well fitted for this Study as the men…by their natural curiosity & the accuracy & quickness of their Sensations’.

Ann Shteir, Sara Sidstone Gronim and Emmanuel Rudolph have all uncovered thousands of women who were active in botany in eighteenth-century North America and Europe, and their work shows how women found many further sources of joy in the pursuit, far beyond the aspects that were considered stereotypically feminine. Botany gave Jane Colden opportunities to physically ‘exert herself,’ rambling long distances alone ‘in a region of rolling upland, pocked by ponds and swamps, punctuated by rocky hills, and crisscrossed by streams’.

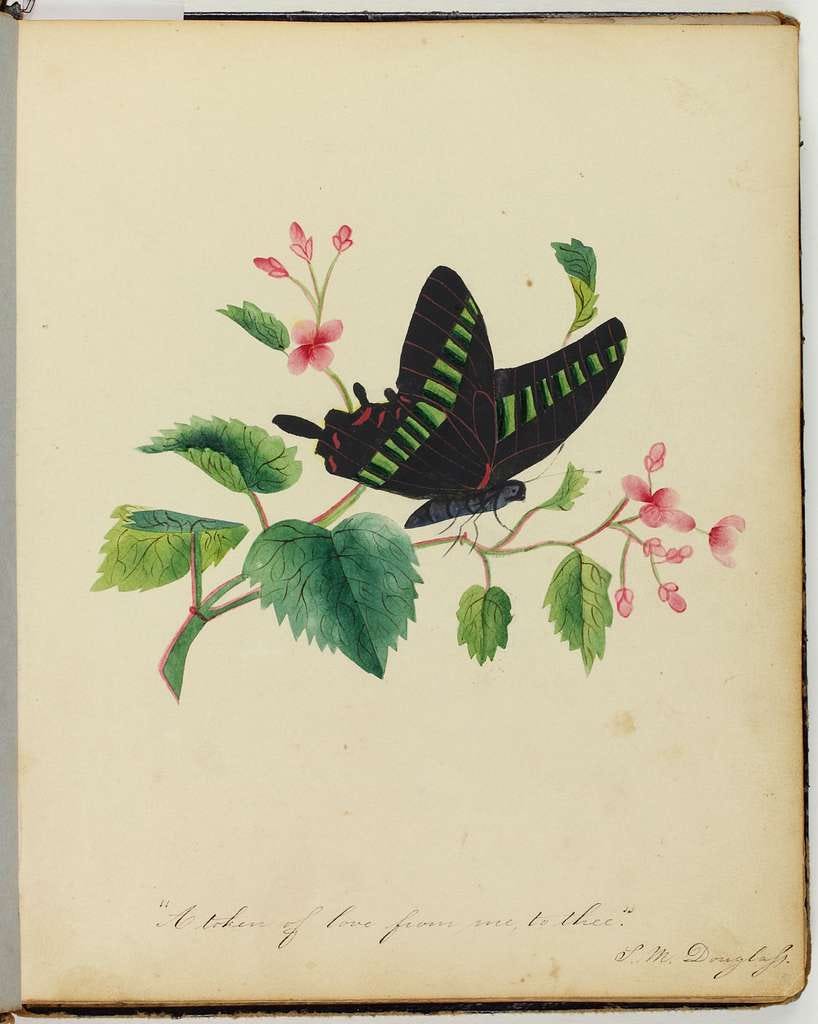

Jane’s experience, that botany was a justification for vigorous (and so-called ‘manly’) exertion and adventure, was shared by many women. In the nineteenth-century, Marianne North (1830-1890) would travel through fifteen countries in the space of fourteen years, during which she taught herself botany, painted vivid scenes of exotic plants in their habitats, and oversaw the design and building of the gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, in London. Women such as Frederica Plunket gave botany as the reason why they wanted to climb some of the Alps’ highest mountains. Botany was also a gateway into the public sphere for women: Jane Colden corresponded with other botanists, male and female, and posthumously achieved some fame as the identifier of a new plant with the local name Gold Thread, which she named Fibraurea. Sarah Mapps Douglass, who was born in 1806 into a Black abolitionist family in Philadelphia, used botany to teach young African American girls and women about the natural sciences in the 1830s, and her own exquisite botanical drawings are some of the earliest examples of signed works of art by African American women.

However, in the mid-nineteenth century, botany was rebranded. No longer ‘just’ an amateur hobby for women, botany was recast into a serious academic subject - for men only. John Lindley was appointed the first professor of botany at University College, London, and he was clear that his intention was to ‘redeem [botany] from the obloquy which has become attached to it’ via its association with women. Lindley kindly permitted women to continue being interested in botany, but he downgraded them into ‘unscientific readers’ who merely needed to teach their ‘little people’. He stressed that the chief studies and innovations in botany would now take place in male-only universities.